Education in the United Arab Emirates

From Dust to Riches: An Introduction to the UAE

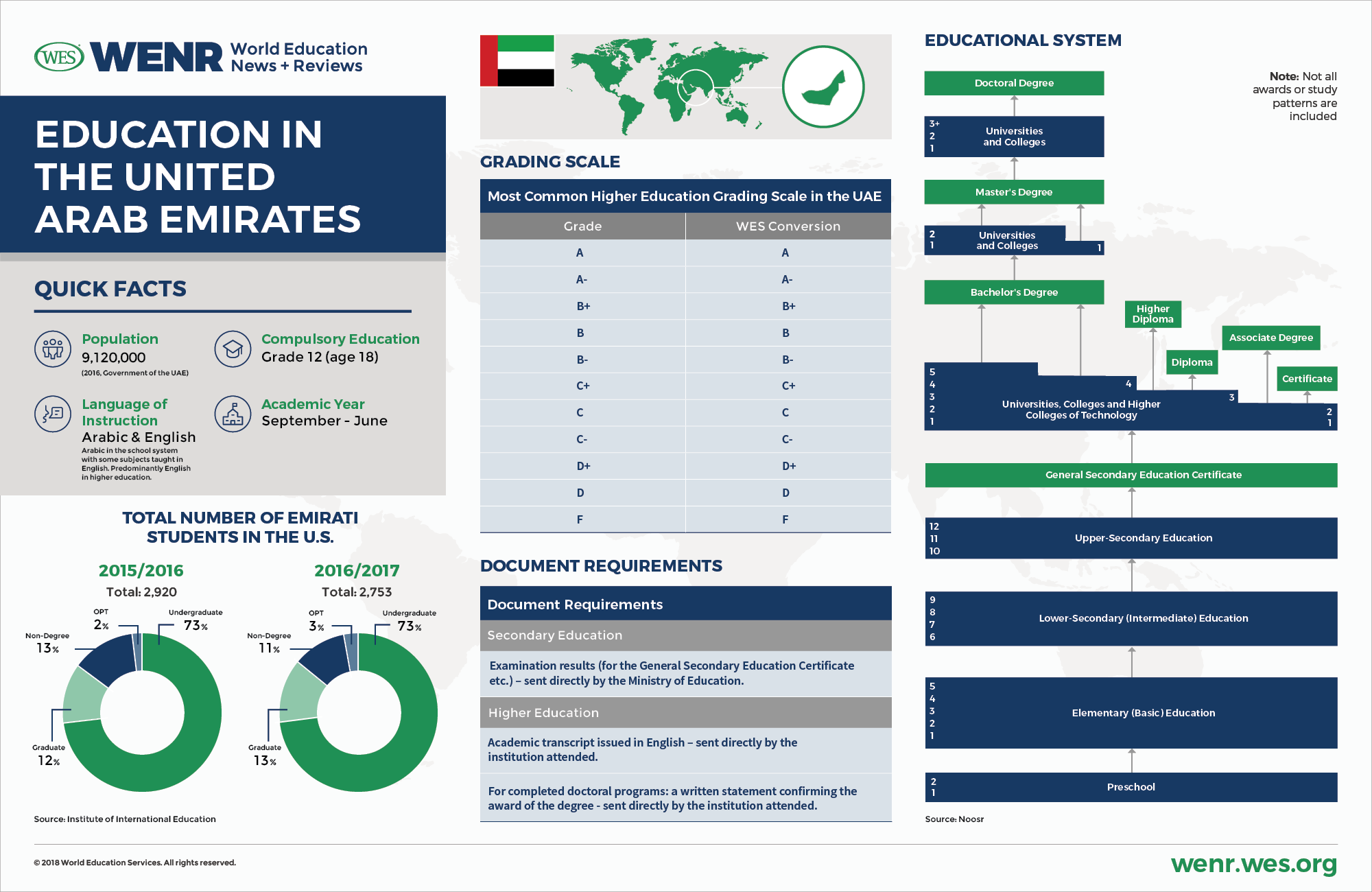

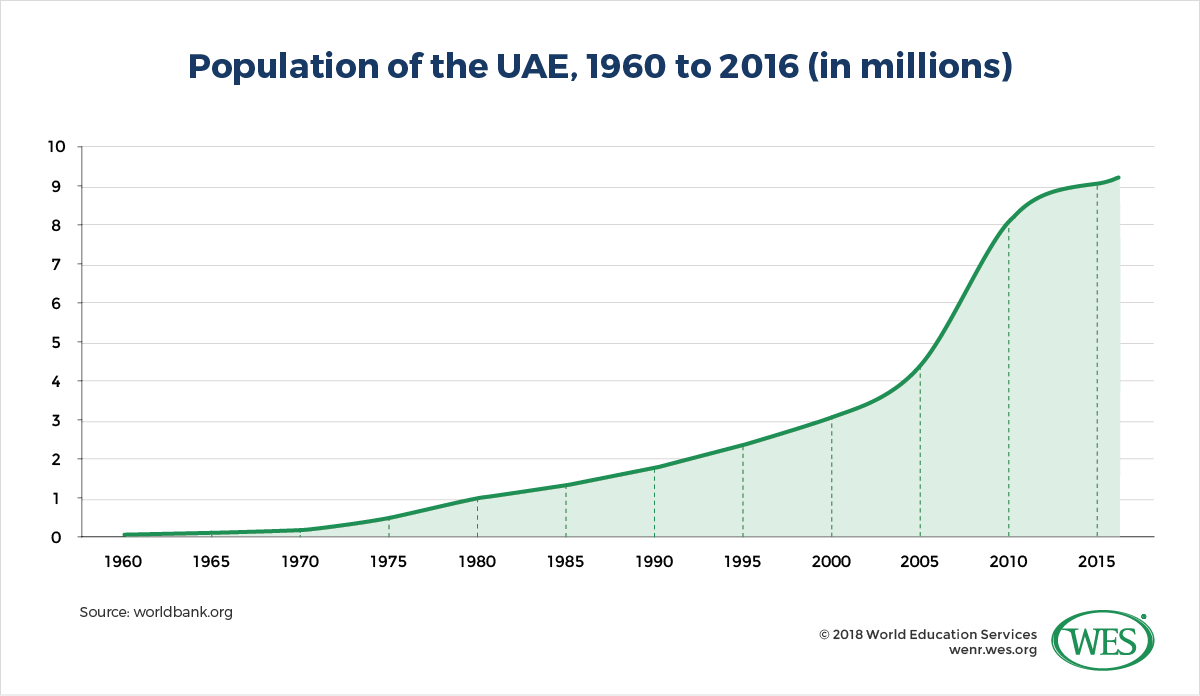

Enriched by oil revenues, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) has undergone a meteoric economic rise over the past decades that transformed the country from a small, backwater desert nation of 279,000 people in 1971 into a rich, vibrant economic center of more than nine million today.

As a kind of testimony to this drastic transformation, most of the UAE’s current residents are foreign-born. Alongside other oil-rich Persian Gulf monarchies like Qatar and Kuwait, the UAE is one of very few countries in the world where migrant workers outnumber the native-born population.

In fact, the UAE now has the sixth-largest migrant stock in the world: Fully 90 percent of the country’s populations are migrants, most of them male laborers from South Asian countries like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. The economic pull from the small Persian Gulf nation has proved so irresistible that the migration corridor between India and the UAE has become the largest such corridor worldwide. Indians now make up more than 25 percent of the total population of the Emirates.

An independent country since 1971, the UAE is a federation of seven hereditary monarchies or emirates that, combined, is smaller than the U.S. state of Maine. The most populous of these emirates is currently Dubai—a sprawling global city whose cosmopolitan resident population has more than doubled since 2006. Sometimes referred to as “Hong Kong in the desert,” Dubai is now home to nearly three million people. It has the world’s tallest building and one of the busiest airports on the globe. Strikingly, fully 70 percent of the population is male. About 37 percent of Dubai’s residents come from India and Pakistan; native Emiratis make up only 8.2 percent of the population.

While Dubai is the most prominent city in the Emirates, the UAE capital is Abu Dhabi, the principal city of the emirate of the same name. With 2.9 million people, Abu Dhabi has a marginally smaller population than Dubai, but the sheikhdom makes up more than 80 percent of the UAE’s geographical area, and, crucially, sits on the vast majority of the UAE’s oil and gas fields.

It is these hydrocarbon resources—estimated to be the seventh-largest in the world—that elevated the UAE to a highly developed country with a GDP per capita that is higher than Italy’s or South Korea’s. At present, the UAE is one of the top-performing economies in the Arab world and is among the world’s 10 largest petroleum producers.

That said, the significance of “black gold” for the country’s economy has decreased over the decades. Oil revenues as a share of GDP have fallen to around 30 percent today and are expected to further decrease to 20 percent by 2021.

Since oil and gas reserves won’t last forever, the Emirates, most notably Dubai, have pursued a systematic economic diversification strategy. Dubai is now the most important financial center and trading hub in the Middle East, going far beyond petrol capital. The UAE now boasts an excellent infrastructure, logistics, and investor-friendly business environment. Sectors like foreign trade, tourism, and banking are expanding quickly. The real estate market has recently slowed, but over the past two decades, construction in major cities boomed to the extent that reportedly 2 percent of the world’s cranes were in Dubai alone. The city is now endowed with a sparkling skyline of high-rise buildings and luxury hotels.

On the downside, much of this construction boom was achieved on the backs of migrant laborers, who often worked under abusive conditions. Human Rights Watch has described the exploitation of guest workers in the UAE as systemic, since the country’s visa system ties migrant workers to their employers. “Those who leave their employers can face punishment for ‘absconding,’ including fines, prison, and deportation,” according to Human Rights Watch.

While construction workers often toil under hazardous conditions, domestic workers face “… a range of abuses, from unpaid wages, confinement to the house, workdays up to 21 hours with no breaks, to physical or sexual assault by employers.” A new law, passed in 2017, seeks to curb abuses of domestic workers, but the extent to which this legislation will improve conditions remains to be seen.

Despite all the modern glitz and flash of Dubai, the UAE still has an archaic and autocratic monarchical political regime in which the dynastic rulers of the seven emirates have largely unlimited executive, legislative, and judicial authority. Political parties and labor unions are banned; media and social media are censored. The judicial system of the Muslim country incorporates elements of Sharia law—offences like adultery and alcohol consumption by Muslims are punished by flogging or even stoning.

Flush with petrol cash to redistribute among its native population, the UAE is among a small group of countries worldwide—many of them oil-rich “rentier states”1 in the Persian Gulf region—that have, thus far, resisted democratization despite achieving the status of a high-income economy. The monarchical regimes in the Persian Gulf region survived the Arab Spring of the early 2010s largely unscathed.

Photo by Miroslav Petrasko.

Education Is a Top Priority in the UAE

To enable further economic growth outside the hydrocarbons sector and create a competitive knowledge-based economy, the government of the UAE has treated education as a top priority for some time. It has used its petrol dollars effectively to increase educational attainment rates and establish a relatively high-quality education system—more or less from the ground up. Sheikh Zayed Bin Sultan Al Nahyan, the UAE’s first president, envisioned education as a key element of economic modernization, noting that the “greatest use that can be made of wealth is to invest it in creating generations of educated and trained people… [T]he prosperity and success of the people are measured by the standard of their education”.

This prioritization is reflected in the UAE’s current strategic education plan for 2017–2021, which seeks to raise the upper-secondary graduation rate to 98 percent (from an already high rate of 96.7 percent in 2016). Ambitiously, the government also seeks to improve the UAE’s ranking in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) study, to score among the top 20 countries. The government’s National Higher Education Strategy 2030 seeks to strengthen accreditation standards, increase research output, establish a qualifications framework, and develop curricula more geared toward employment in consultation with the business sector.

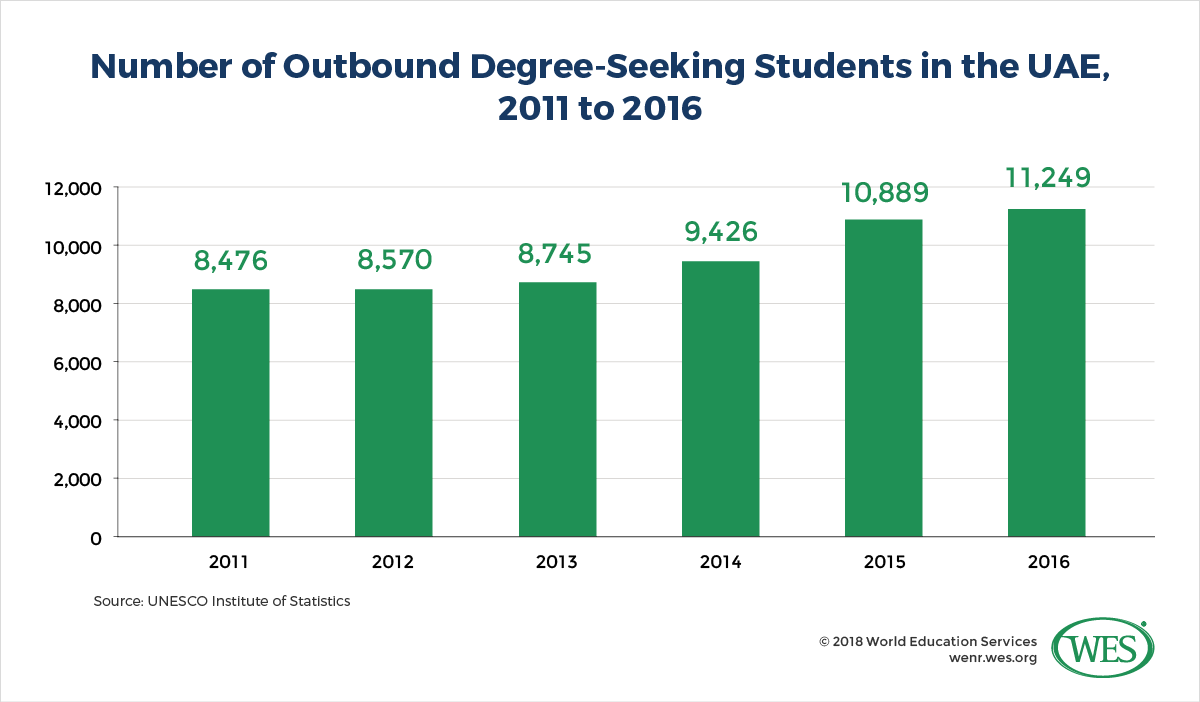

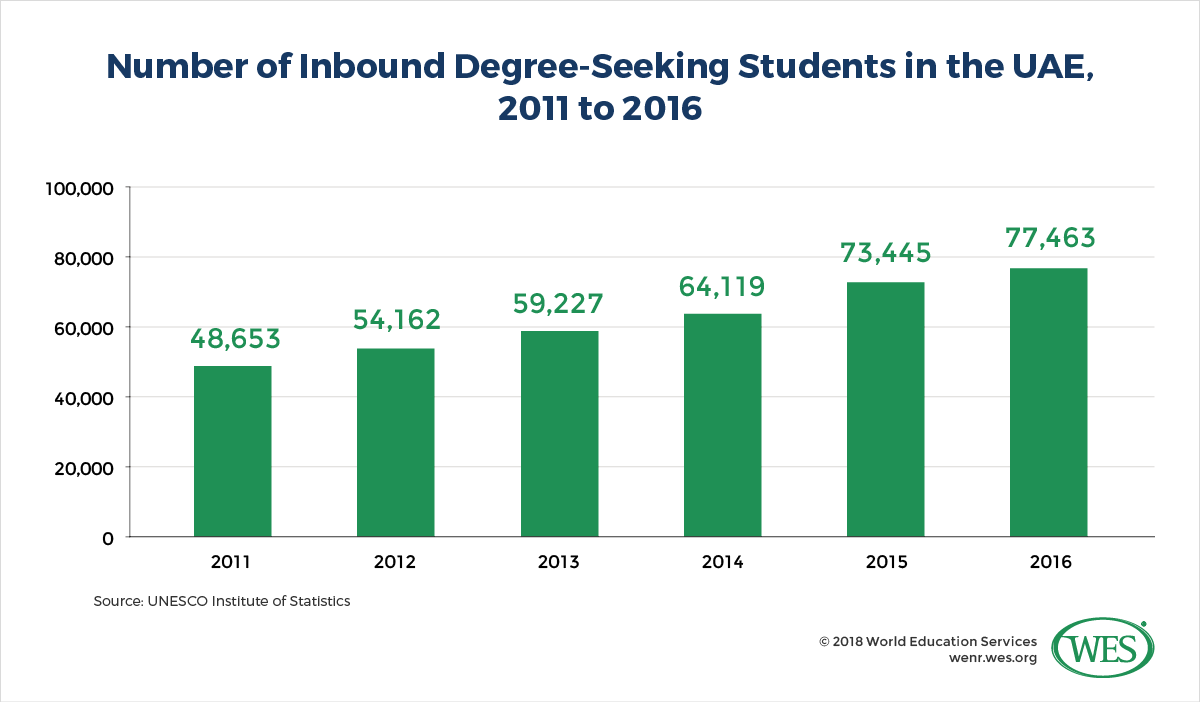

The UAE also pursues a highly effective internationalization strategy and has become one of the preeminent transnational education hubs in the world. In a recent comparative study of 38 education systems worldwide, the British Council ranked the UAE highly favorably in terms of regulatory frameworks for student mobility, openness to transnational education, and recognition procedures for foreign degrees. Underscoring that assessment, the UAE has witnessed rapidly increasing outbound and inbound student flows over the past decade. Inbound mobility in particular has been rising sharply.

Outbound Student Mobility Is Growing Fast

By international standards, the UAE has a high outbound student mobility ratio: The percentage of Emirati nationals studying in tertiary degree programs abroad was 7.1 in 2016, compared with only 1.9 in China and 0.9 in India, the world’s two top-sending countries of international students in terms of volume, according to UNESCO. The total number of Emirati students enrolled in degree programs abroad more than doubled between 2004 and 2016, from 4,835 to 11,249. Between 2012 and 2016 alone, the number of outbound students increased by 31 percent.

The most popular destination countries among Emirati degree-seeking students are the U.K. and the U.S.: In 2016, enrollments in these two countries accounted for fully 30 percent and 27.5 percent, respectively. India was a distant third with 13 percent, followed by Australia, Oman, and Germany, according to UNESCO.

Data from the Institute of International Education’s Open Doors show that the number of Emirati students in the U.S. has fluctuated over the past 15 years, while generally trending upward. There were 2,753 Emirati students in the U.S. in the 2016/17 academic year, compared with only 1,653 in 2009/10. However, these numbers have most recently dropped again: After solid growth throughout the first half of the 2010s, the number of Emirati students declined by 5.7 percent between 2015/16 and 2016/17.

Current student visa data provided by the Department of Homeland Security show that students from the Emirates are almost exclusively male (90.6 percent). The overwhelming majority (74.2 percent) study at the undergraduate level with 45 percent of students enrolled in STEM fields.

The growing outbound mobility in the UAE is likely driven by rising tertiary enrollment rates and an increasing student population, as well as by mounting interest in pursuing a top-quality foreign education as a means of improving employment prospects. Emirati employers reportedly prefer international graduates over graduates of local private institutions. Some employers also sponsor students’ overseas study in fields like engineering with funds and job offers upon graduation. Government bodies and academic institutions similarly facilitate students’ outbound mobility with a wide range of scholarship programs, many of them granted to students at public universities heading to countries like the U.S. and Canada.

Growing interest in foreign education is also reflected in the increased demand for international elementary and secondary schools in the Emirates. Remarkably, the UAE currently has the highest number of international schools worldwide after China, most of them teaching British and U.S. curricula in English. There were 624 international schools with 627,800 enrolled students in the UAE as of January 2018 (up from 548 schools with 545,074 students in 2016). The vast majority of these schools are located in urban centers like Dubai, but international schools are spreading elsewhere as well.

While these schools mostly cater to the UAE’s surging expatriate population, the number of Emirati nationals enrolling in them is rising and made up 17 percent of all enrollments in 2014/15. By some accounts, more than 90 percent of students at international schools intend to study overseas after graduation, so this trend will most likely accelerate tertiary mobility.

The outlook for outbound mobility, thus, is favorable and underpinned by the growing demand for education overall. The UAE is currently riding the tail end of a youth bulge phase with more than 30 percent of the native population still under the age of 25. The country’s tertiary gross enrollment ratio (GER) jumped from 17.4 percent in 2007 to 36.8 percent in 2016, while the total number of tertiary students grew from 113,648 in 2011 to 159,553 in 2016, according to UNESCO. Although almost half of these students are foreign nationals, further increases in enrollments among the native-born population are likely in the years ahead. By some estimates, the number of students at all levels of education in the UAE will rise at an annual growth rate of more than 4 percent until 2020 alone.

Inbound Student Mobility: One of the Highest Mobility Ratios in the World

Inbound student mobility to the UAE is enormous and growing at high velocity. As a small country, the UAE has lower total international student numbers than major international study destinations like the United States, the United Kingdom, or Australia. But its inbound mobility ratio of 48.6 percent is easily one of the highest in the world and dwarfs that of all major destinations. The number of international degree-seeking students in the UAE recently spiked from 48,653 in 2011 to 77,463 in 2016, according to data from UNESCO. Illustrative of this development, the American University of Sharjah, a reputable UAE institution, is now said to be the university with the largest share of foreign students in the entire world: 84 percent of its student body consists of international students.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given current trends in labor migration, India is by far the largest country of origin of foreign degree-seeking students in the UAE: The number of Indians enrolled in degree programs in the Emirates has increased by 50 percent since 2011. As per UNESCO, Indians now make up 17 percent (13,370 students in 2016) of all international students. Other top-sending countries are Middle Eastern, like Syria, Jordan, Egypt, and Oman (all sending more than 5,000 students), followed by Pakistan.

Employment opportunities for highly skilled workers in its diversifying economy make the UAE an attractive study destination for students from other countries. Also turning the UAE into a magnet for foreign students is the country’s number of high-quality universities included in international rankings, such as United Arab Emirates University and the University of Sharjah, as well as a range of branch campuses of top universities globally, including New York University, Sorbonne-Université, and Australia’s University of Wollongong (see also the transnational education section below).

This puts the UAE in a good position to accommodate excess demand for education in youth-bulging countries in the Middle Eastern region, many of which are currently suffering from high youth unemployment rates. The UAE is now the top study destination of international students from Arab countries like Egypt, Jordan, and Oman.

This trend persists despite the fact that the UAE is anything but a low-cost study destination. Mindful of this barrier, the government seeks to attract students by offering generous visa policies. Since 2016, foreign students have been allowed to work part time for designated employers. In 2018, the government also drastically extended its one-year residency visa for foreign university graduates: Exceptionally talented students will now “be eligible for a 10-year residency, while other students can get a five-year visa, and dependents [of guest workers] will receive a visa extension to help them get started on their career after graduating.” Universities and government institutions also offer an increasing variety of scholarships for international students.

However, despite such opportunities and a broad assortment of high-quality study options, the UAE’s international student stock is, as of now, not overly diverse. Aside from India, a Hindu country with a large Muslim minority, the vast majority of international students in the UAE come from Muslim-majority countries (more than 66 percent in 2016). The number of students from nearby China, the largest sender of international students worldwide, and other East Asian countries is still marginal. China is currently not even represented among the top 25 sending countries to the UAE. It remains to be seen if recent “strategic partnership” agreements between the UAE and China will result in greater student inflows from China in the years ahead.

Transnational Education in the UAE: A Hub of Global Scale

The UAE is a major hub for transnational education (TNE). Until 2015, when it was overtaken by China, the UAE hosted the largest number of foreign branch campuses in the world. Most of these campuses are located in so-called free zones like the Dubai International Academic City and the Dubai Knowledge Village. These are free trade zones with state-of-the art infrastructure specifically dedicated to education and human resources development. They were created beginning in the early 2000s to incentivize foreign providers to set up shop in the UAE.

As of 2017, Dubai alone had 10 free zones with 39 institutions, including 24 foreign branch campuses from 12 different countries. The latest foreign university to open a campus in a Dubai free zone was the British University of Birmingham in 2018.

Other foreign institutions operating in the UAE include the New York Institute of Technology, Rochester Institute of Technology, Canadian University Dubai, Heriot-Watt University, Middlesex University, the Swiss École Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Indian institutions like the Birla Institute of Technology and Science and the Institute of Management Technology, Iran’s Islamic Azad University, and several other providers.

While private universities operating outside of these zones are bound by mandatory UAE accreditation requirements, foreign-owned institutions in free zones have more freedom. They are also exempt from corporate and income taxes and can fully repatriate their profits. Unlike in countries like China, where the government pushes partnerships with Chinese universities and imposes a number of restrictions on TNE providers, the UAE prefers TNE providers to autonomously offer the same academic programs in the Emirates as on their home campuses. Other forms of TNE, like joint and dual degree programs, are less common in the UAE.2

A number of branch campuses are located outside of free zones, and several providers even within the free zones have voluntarily obtained accreditation of their programs by the UAE’s federal Commission for Academic Accreditation (CAA). Quality oversight in the zones, however, varies by emirate. While branch campuses in the free zone of the emirate Ras Al Khaimah faced few regulations until very recently, Dubai has required providers to be authorized and licensed by its Knowledge and Human Development Authority (KHDA) for some time.

KHDA conducts quality inspections in the free zones and has shut down a number of foreign institutions in recent years. The main quality criterion is that academic programs on branch campuses are the same as accredited programs taught on home campuses.

The majority of students at TNE institutions are expatriates and international students. Fully 40 percent of Dubai’s international students study at branch campuses in free zones. That said, the number of Emiratis studying at these institutions is also growing—more than 30 percent of students enrolled at institutions in Dubai’s free zones were Emiratis in 2017. The fact that degrees from KHDA-authorized institutions in free zones have been treated as recognized academic qualifications in Dubai since 2012 has greatly increased the utility of these degrees for Emiratis.

Despite growing demand, however, the overcrowded TNE market in the UAE can sometimes be risky and competitive for foreign providers with increasing numbers of institutions vying for students. Institutions like the University of Michigan were forced to close down their campuses when Dubai experienced an economic crisis and student numbers dwindled following the global financial meltdown of the late 2000s.

IN BRIEF: THE EDUCATION SYSTEM OF THE UAE

The education system of the UAE is young and like the country as a whole has undergone monumental changes over the past 50 years. Historically, education in the region was strongly influenced by Islam and took place in mosques or study circles led by Imams. More modern forms of schooling started to slowly appear in the sheikhdoms in the first half of the 20th century, but education was still limited to a small number of formal schools, most of which catered to male students.

It was not before the discovery of oil and independence from Britain in 1971 that the Emirates started to build a modern, mass-scale education system. Newly found petrol wealth enabled the UAE to create a public education system akin to Western systems within just a few decades—essentially at warp speed. Today, the structure of the education system closely resembles that of the U.S.: It features a K-12 school system, two-year associate degrees, four-year bachelor’s degrees, two-year master’s degrees, and doctoral degrees.

Progress in improving education has been rapid and extensive. The country’s adult literacy rate jumped from 32 percent among women and 57 percent among men in 1975 to above 90 percent for both in 2005, according to UNESCO. The female youth literacy rate in that year stood at 97 percent, far higher than the current global average of 86 percent.

The Administration of the Education System

The UAE is a federation of seven autonomous states that vary considerably in their population size and economic development. Aside from Abu Dhabi and Dubai, they include the smaller emirates of Ajman, Fujairah, Ras Al Khaimah, Sharjah and Umm Al Quwain located in the north of the country.

The ruling monarchs of the seven sheikhdoms form the Federal Supreme Council, the UAE’s core decision-making body that elects the country’s president and prime minister. The president is elected for a term of five years, but the position is de facto hereditary and has been held by the emir of Abu Dhabi, the main oil producer of the UAE, since its inception.

All emirates have a high degree of political autonomy in a variety of areas, including education—a fact that presents considerable challenges to the standardization of education between the different sheikhdoms. That said, the harmonization of education systems is currently a high priority, and the country is on its way to establishing a more uniform, nationwide system directed by federal institutions.

In the smaller, northern emirates, the federal Ministry of Education (MOE) already supervises all forms of education, from elementary school to university, and sets curricula, admissions standards, and graduation requirements in the school system. However, the emirates also have their own regulatory authorities, such as Dubai’s KHDA, the Dubai Education Council, or Abu Dhabi’s Department of Education and Knowledge (ADEK). Significant variances therefore still exist between some of the emirates. Notably, the school curriculum of Abu Dhabi differed from the national curriculum, but it was announced in 2017 that curricula would in 2018 be harmonized in a new Emirati School Model.

Private schools in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, likewise, fall under the purview of ADEK and KHDA, while they are overseen by the federal MOE in the other emirates. Private institutions are generally not under direct government control, but are nevertheless bound by guidelines set forth by the federal ministry and local authorities.

The Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research, a separate federal ministry, until recently oversaw higher education, but that ministry was folded into the MOE in 2016. The MOE is thus now the country’s dedicated authority of developing policies related to higher education and research. It licenses higher education institutions (HEIs) and regulates the establishment of federal public institutions, which the MOE funds. That said, the individual emirates can also set up public institutions that they fund through their local emirate governments. Abu Dhabi’s ADEK has the right to “establish academic institutes and educational bodies in Abu Dhabi, in coordination with MOE and with approval from the Executive Council.”

The MOE’s CAA is tasked with licensing non-federal HEIs and accrediting individual study programs at non-federal public and private institutions nationwide. Quality assurance in Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), on the other hand, has recently been shifted to a federal Vocational Education and Training Awards Council (VETAC). However, local authorities like the KHDA and the Abu Dhabi Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (ACTVET) are also authorized to regulate TVET within their respective jurisdictions.

Compulsory Education Age, Language of Instruction and the Academic Calendar

School education is a constitutionally guaranteed right of every Emirati citizen and provided free of charge at public schools. Education is compulsory for all children from the age of six to completion of grade 12 (or the age of 18). The language of instruction at Emirati public schools is Arabic in most subjects, although the numerous private schools and universities in the Emirates also teach in English and other languages. In higher education, English is the main language of instruction.

The academic year in the UAE runs from September to June at public schools and HEIs alike. Since 2010, the school year has been divided into three semesters comprising 180 days of instruction in total. There is a three-week break in December and a two-week break in March. Schools are closed for most of July and August. As in several other Muslim countries, Friday and Saturday are weekly days off, while Sunday is a regular day for school and work.

In contrast to public schools, private international schools usually follow a two-semester system (also running from September to June), while some private schools in Dubai have an altogether different semester schedule that runs from April to March. Universities typically have full-length spring and fall semesters and a shorter summer semester in-between. Most international providers accommodate the local system, but some may have different semester schedules.

Elementary and Lower-Secondary Education (Basic and Intermediate Cycles)

Elementary education is open to all children that are at least six years of age. Non-Emirati nationals may attend public schools but have to pay fees, whereas public education is free for Emiratis. Before entering school, children can attend two years of kindergarten (ages four and five); preschool education is not mandatory in the UAE.

Elementary education (basic education) lasts five years (grades one to five). The language of instruction is Arabic, which is taught alongside English starting in the first grade under the new national curriculum. Other subjects taught in the elementary cycle include Islamic education, integrated social studies, mathematics, science, music, and physical education. At public schools, boys and girls are instructed separately in segregated classes in all grades. Promotion and graduation are earned based on results of continual assessments and semester- and year-end examinations.

Lower-secondary education (intermediate education) follows elementary education and lasts four years (grades six to nine). Students must graduate from grade five to be admitted—there are no separate entrance examinations at public schools at this stage. The subjects studied are mostly the same as in the elementary cycle, although subjects like health sciences or business management may be introduced, while subjects like music may no longer be offered. As in the elementary cycle, promotion and graduation are earned based on continual assessments and semester- and year-end examinations. Upon completion of grade nine, students have the option of enrolling in technical secondary schools or continuing their studies in the academic track.

Technical Upper-Secondary Education

While it may be possible for students to transfer into the vocational track early on in the intermediate cycle, this is not the predominant model in the UAE. Study at technical secondary schools typically begins after grade nine for three additional years of upper-secondary schooling (grades 10 to 12). Technical schools offer programs that are more geared toward employment, and usually involve study in vocational specialization subjects in addition to core academic subjects like mathematics, science, Arabic, and English. Some schools require students to pass an entrance examination to be admitted.

Vocational specializations offered at technical secondary schools include a variety of business-related majors (accounting and finance, human resources management, etc.), as well as engineering, computer technology, tourism, foreign languages, health sciences, aviation management, and others. Upon passing the final graduation examination at the end of grade 12, students are awarded the Secondary Technical School Certificate, a credential that qualifies students for tertiary education. At some institutions, such as technical secondary schools that Abu Dhabi’s ACTVET oversees, students may also concurrently earn a recognized Australian vocational trade certificate. These programs are currently in high demand.

General Upper-Secondary Education

Upper-secondary education in the general academic track is currently undergoing a number of changes. Until recently, students had the option of choosing between a scientific and a literary stream; however, since 2015 these streams have been eliminated. Students are now placed into either a general or an advanced track based on their academic performance in grade nine.

Students in the advanced track receive more in-depth instruction in mathematics and science, to better prepare them for university study in disciplines like engineering, medicine, and the natural sciences. The change is part of the government’s drive to nurture 21st century skills and foster “knowledge integration in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and other fields” with the goal of strengthening the country’s knowledge economy.

Upper-secondary education lasts three years (grades 10 to 12), during which students typically receive six hours of instruction each school day. Subjects include Arabic, English, Islamic education, mathematics, social sciences, information technology, health sciences, physical education, and the arts and science subjects ( which differ between the two tracks). Although the language of instruction is Arabic, mathematics and science are taught in English under the Emirati School Model curriculum currently being phased in.

At the end of the program, all students in public schools and private schools that follow the national curriculum sit for a nationwide external examination. Graduates are awarded the General Secondary Education Certificate (known in Arabic as Tawjihiyya or Thanawiyya Al-A’ama).

University Admissions

In addition to the grade 12 graduation examinations, students at public schools and private schools that follow the national curriculum must, since 2017, sit for the Emirates Standardized Test (EmSAT), which is a prerequisite for admission into most public universities and colleges.

EmSAT is a series of standardized computer-based tests that replaces the Common Educational Proficiency Assessment (CEPA), the test previously used to determine eligibility for college admission. EmSAT is also administered in lower grades to measure overall student and school performance. In grade 12, students must take the EmSAT in mathematics, physics, English, and Arabic, with students in the advanced track also required to take the test in chemistry.

Current reforms, including the introduction of EmSAT, are a departure from previous admissions practices at public HEIs. Admission to public universities and colleges in the UAE is highly selective—institutions commonly require high minimum scores in exit examinations (CEPA, now EmSAT).3 Since English is the main language of instruction, they also require minimum scores in English proficiency tests like the TOEFL or IELTS. Beyond that, some institutions may impose additional entrance examinations.

Until now, students who did not meet these requirements had to complete a foundation program before being admitted. Depending on the academic preparedness of the student, foundation programs lasted between one and four semesters and covered subjects like Arabic and mathematics, but its foremost emphasis was English, since English is the main language of instruction at HEIs and students frequently lack proficiency. Merely 10 percent of students were eligible for direct entry in 2010, although that number improved to a still low 23 percent in 2016.

Despite these low entry rates, the foundation program is being phased out beginning in 2018, and will be completely shut down by 2021. One reason for ending the foundation program is cost: It has been estimated that foundation programs took up some 30 percent of higher education spending. Emirati authorities also believe that the new national school curriculum with its emphasis on English language instruction will greatly increase students’ preparedness, and that almost all students will be eligible for direct entry at public institutions in the years ahead.

Failing that, abolishing the foundation year might further increase enrollments at private institutions despite the fact that private HEIs are much more expensive compared with tuition-free public schools. Admissions standards at private HEIs can be lower, even though English language proficiency needs to be demonstrated at most of those institutions as well (via the TOEFL, IELTS and other tests). However, students at private HEIs can take advantage of foundation-like bridge courses offered by many of these institutions, or be admitted conditionally.

Overall, admissions requirements at private institutions vary widely, but at the very minimum the General Secondary Education Certificate is required, as are, almost always, demonstrated English language skills. Many private universities have more demanding requirements, including entrance examinations or SAT or EmSAT scores.

Scrapping the foundation year may also increase the already booming demand for study at international high schools that offer English-taught curricula. Holders of foreign high school qualifications like a U.S. high school diploma, the British IGCSE (International General Certificate of Secondary Education), or the International Baccalaureate (IB) are eligible for admission at public Emirati institutions, but they may have to submit SAT or ACT scores and fulfill additional requirements at individual institutions.

Private Schools in the K-12 System

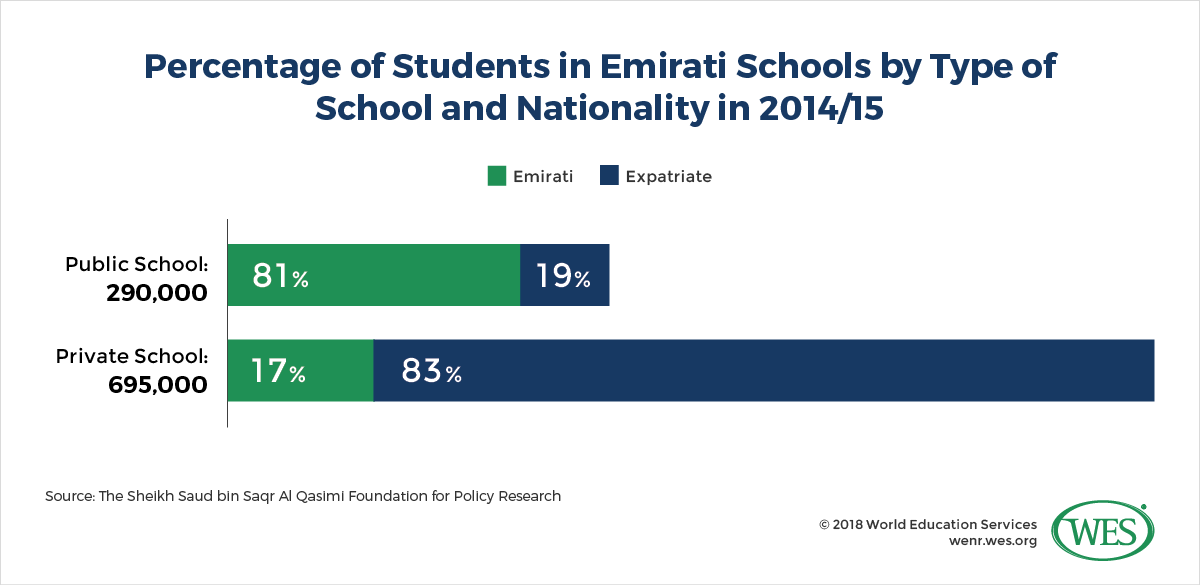

The share of private sector enrollments in the UAE’s school system is high. In 2015, 71 percent of all elementary and secondary students studied in private schools. A majority of these students are enrolled in elementary schools, but enrollments in private upper-secondary schools also accounted for more than 61 percent in 2016, according to UNESCO.

This share is likely to increase even further since private enrollments are growing fast. Between 2009 and 2014, the number of students enrolled in private schools in the K-12 system grew by about 7 percent annually, far outpacing growth rates at public schools. The professional services firm PricewaterhouseCoopers estimated in 2016 that 175,000 additional school seats would be required in the UAE by 2020, and 90 percent of them are expected to be created in the private sector. In Dubai, fully 90 percent of students studied at private schools in the 2015/16 academic year.4

The private sector is dominated by for-profit international schools. In Dubai, for instance, private schools following the national UAE curriculum accounted for only 5.6 percent of enrollments in 2015/16, while schools offering U.K., U.S., Indian, French, and IB curricula enrolled more than 86 percent of all 265,299 private sector students in the emirate. Other curricula available at international schools include those of Germany, the Philippines, and Pakistan. Overall, 17 different curricula are offered at private schools in Dubai, with the Indian, U.K., and U.S. curricula being the most popular. In Abu Dhabi, private schools offered 14 different curricula in 2015.

The vast majority of students in international schools are expatriates; Emiratis accounted for only 17 percent of students in 2015/16. But as mentioned before, the number of Emiratis studying at these schools is growing rapidly: Between 2003 and 2010, the number of Emiratis enrolled at private schools in Dubai alone increased by 75 percent.

International schools are licensed and overseen by the KHDA in Dubai, ADEK in Abu Dhabi, and the federal MOE in the northern Emirates. Private providers undergo quality audits, most notably in Dubai, where KHDA’s Dubai School Inspection Bureau conducts annual site visits. Low-performing schools may be penalized with admission freezes and tuition caps. Beyond that, private providers face few curricular restrictions except that they must offer Arabic and Islamic Studies classes for Muslims. However, current reform initiatives could curtail these freedoms soon. Emirati authorities intend to align private school curricula, including those of international schools, with the new national curriculum after a two-year grace period.

Private schooling in the UAE is now a multi-billion dollar industry, partly because of sharply rising tuition fees over the past years. In Dubai alone, private providers raked in more than USD $2 billion in revenues in 2017/18 (up from USD $1.28 billion in 2013/14). Tuition fees in Dubai currently range anywhere from USD $675 to USD $32,711 annually, with IB schools tending to be the most expensive. Some schools recently hiked fees so drastically that the KDHA in 2018 enacted a freeze on tuition fees for the 2018/19 academic year.

HIGHER EDUCATION

The first higher education institution founded in the UAE was the United Arab Emirates University in Abu Dhabi, which was established in 1976. Since 1990, when there were five HEIs, the number of institutions has grown at a rapid pace to more than 70 today. The present higher education landscape is somewhat transient with new institutions opening, while others are closing or merging. As of March 2018, the MOE listed 72 licensed HEIs, while the CAA currently lists 76 institutions.

The total number of tertiary students in the UAE doubled between 2007 and 2016, from 80,296 to 159,553. According to the latest UNESCO data (2016), students are enrolled predominantly at the undergraduate level—only 13.6 percent and less than 1 percent of students studied at the master’s and doctoral levels, respectively. The population-rich emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi have almost 60 percent of all students. The field of study most pursued in the UAE by far is business and economics, followed by engineering and education.

Public Higher Education Institutions

There are three federal institutions under direct control of the MOE: the UAE University, Zayed University, and the Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT), a group of 17 colleges located across the UAE. Founded in 1988, HCT is the largest HEI in the country with 23,509 students in 2016/17. Its colleges are segregated by sex; HCT comprises nine colleges for women and eight for men, and is only open to Emirati nationals. Women now make up more than 60 percent of the student body (see also the sidebar on women in education). The institution offers programs geared toward employment that lead to diplomas, higher diplomas, applied bachelor’s degrees, and more recently, master’s degrees.

On the other hand, UAE University, considered one of the UAE’s best research universities, awards degrees in all education cycles, including doctoral degrees. Zayed University was originally a women’s university, but it now also admits men as well as international applicants. It offers bachelor’s and master’s programs, but no doctoral programs.

In addition to these three federal universities, there are a number of HEIs founded by governments in the different emirates, including Al Qasimia University and Khalifa University (which in 2017 merged with the Petroleum Institute and Masdar Institute of Science and Technology into the Khalifa University of Science and Technology). These types of institutions are difficult to classify; several need to be considered not public but semi-public, since large parts of their revenues are derived from private sources.

Private Higher Education Institutions

The prominence of private HEIs in the UAE has been discussed elsewhere in this article. Suffice it to say, the vast majority of HEIs in the Emirates are privately owned; many are for-profit institutions. More than 70 percent of all private institutions are located in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, a majority of them in free zones, including a large number of foreign branch campuses. Emirati authorities in recent years lobbied intensively, especially prestigious schools, to attract these branch campuses. Abu Dhabi, for instance, bankrolled in its entirety “the best campus that money can buy” for New York University’s overseas venture in the UAE.

In light of such developments, the growth of enrollments at private institutions has outpaced that of public HEIs by significant margins in recent years. As of 2016, fully 70 percent of all tertiary students in the UAE were enrolled in private institutions, according to UNESCO. Most of these students are expatriates and international students—only 37.5 percent of private sector students in Dubai, for instance, were Emirati nationals in 2017. However, the total number of Emiratis studying at private institutions is growing: In Dubai, there were 22,618 UAE nationals enrolled in private HEIs in 2015/16, compared with only 10,943 students in 2011.

Teaching Staff

One remarkable feature of Emirati internationalization, and one not often seen in other countries, is the fact that the country’s tertiary teaching staff is now almost exclusively foreign-born, even at public institutions: 98 percent and 92 percent of instructors in private and public institutions were expatriates in 2014, according to a report by the Islamic investment bank GFH. While the government has imposed a systematic Emiratization policy that seeks to increase the percentage of Emirati employees with quotas in both the public and private sectors, the policy doesn’t appear to be enforced in the education system. Foreign instructors are lured to the UAE with tax-free salaries comparable to those paid in Western countries. Other generous benefits include free housing and health insurance, and 60 days of paid vacation every year.

However, the employment of foreign teachers is not without conflict, since instructors from Western countries, in particular, are used to academic freedom and a more permissive academic environment. In recent years, a number of incidents occurred involving professors having their visas denied for undisclosed reasons—though political motives were suspected. As an Italian researcher noted in an interview with Al-Fanar Media in 2017, “It is very hard … to have lecturers speak in the classroom about sensitive topics, whether that is regional politics, press freedom, the U.S. travel ban, or other similar topics … and things became much more sensitive in the wake of the Arab Spring.”

Female Participation in Education: Women Now Outnumber Men

As in other conservative male-dominated societies, women in the UAE have traditionally been discriminated against in a variety of ways. They encounter barriers to labor force participation, and have only limited social, economic, and cultural rights. Domestic violence, for instance, remains legal, and in marriage wives have an inferior status and fewer rights than husbands.

However, the UAE has made significant strides over the past decades and now ranks relatively favorably in terms of gender equality by regional standards (ahead of countries like Turkey, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia).

One area in which great progress has been made is female participation in education. While enrollment rates among women in both school and higher education were abysmal in the 1970s, they now graduate from secondary school in higher numbers than men (at a ratio of 6 to 4). In higher education, likewise, women now outnumber men: Between 2012 and 2014, the percentage of tertiary enrollments by women shot up from 42 percent to 58 percent.

Looking at public Emirati institutions in isolation, this imbalance is even more striking: Not less than 80 percent to 90 percent of students at the UAE’s three federal HEIs are women. At UAE University, for instance, the percentage of female students reportedly increased from 38 percent in 1977 to 82 percent in 2016. In contrast to many other countries, women even outnumber men in STEM disciplines.

Yet, while the female participation rate in tertiary education is much higher than in Western countries like the U.S. or Germany, it is, at the same time, a reflection of relatively low employment rates among women in the UAE. The labor participation rate among women stood at 42 percent in 2016, an enormous increase from only 2.2 percent in 1975, but far below the participation rate of 91 percent among men.

This imbalance belies the fact that women outperform men in secondary school, and a majority of female workers are highly skilled professionals. One reason why there are so few men in higher education is simply the fact that Emirati men find it much easier than women to find employment opportunities right after high school. While the Emirati government encourages women to pursue education and promotes their socioeconomic inclusion, women still remain significantly underrepresented in the labor market and in leadership positions.

Quality Assurance and Accreditation

The rapid proliferation of foreign branch campuses in the UAE has been described as a Wild West gold rush, and has raised concerns about the quality of education at these institutions. Analysts like Philip G. Altbach noted in 2010 that the programs offered at branch campuses “rarely come close to home products in terms of breadth of curriculum, quality of academic staff, physical environment, learning resources and social facilities.” In 2014, the Dubai branch campus of the British Strathclyde Business School, for example, was likened to “little more than an administrative outpost of a foreign institution,” offering just one course out of rented offices.

To alleviate such quality concerns, almost all emirates have in recent years established at least some quality assurance mechanisms for foreign branch campuses. The baseline requirement for HEIs in most free zones is that foreign providers need to be fully accredited in their home countries. Abu Dhabi has generally been more restrictive in the types of foreign providers it invites to its free zones. It also takes an interventionist approach, and focuses on attracting reputable providers and requires them to be federally licensed by the CAA. By contrast, Ras Al Khaimah until recently followed a free market model, imposing few restrictions on free-zone providers. However, in 2017 the emirate amped up quality controls on foreign HEIs.

Dubai in 2008 established a University and Quality Assurance International Board (UQAIB) under KHDA. UQAIB consists of independent, international higher education experts from various countries. It makes recommendations on the basis of which KHDA issues licenses to foreign free zone HEIs and approves programs offered by these providers. Authorization is granted for initial one-year periods that can be extended to three and five years once HEIs graduate their first student cohorts (for more information, see the UQAIB quality assurance manual).

The core quality criterion for branch campuses is that they have “institutional policies, practices and resources in place that are consistent with the … [home institution] and that … create learning conditions for students that are similarly conducive to student success as the learning conditions [of the home institution].” UQAIB conducts on-site audits and may place HEIs on probation or suspend their licenses. In addition, UQAIB must individually approve all study programs—although the requirement that they be comparable to degree programs offered on home campuses can be waived, and unique programs may under certain circumstances be endorsed.

Whereas the quality of free zone providers is generally monitored by the individual emirates, all non-federal HEIs operating outside of free zones must be federally licensed and have their degree programs accredited by the CAA. Established in 1999, the CAA is a government agency under the federal MOE. In order to be licensed by the CAA, HEIs must meet 11 threshold criteria that include transparent governance structures, policies and procedures, adequate teaching facilities, funding, faculty and class sizes, consistent admission policies, and internal quality assurance and reporting mechanisms. Furthermore, HEIs must offer structured credit-bearing programs that include a general education component at the undergraduate level, and a focus on research in graduate programs (for more detail, see the CAA’s Standards for Licensure and Accreditation). Licenses need to be renewed every five years.

In order to advertise programs, enroll students, and have their degrees recognized throughout the UAE, non-federal HEIs must also seek CAA accreditation of their individual degree programs after receiving their initial license. Initially accredited programs are reviewed upon the graduation of the first student cohort, after which they may be accredited for up to five years. The licensing of HEIs is contingent on the continued accreditation of their programs.

Institutions and individual programs can be placed on probation, during which they are not allowed to admit new students and must rectify identified deficiencies or lose their license or accreditation. The CAA maintains public databases for both licensed institutions and accredited programs.

To further foster academic quality, the UAE government recently announced plans to create a national ranking system for all licensed HEIs. The ranking system is expected to be launched in late 2018 and will rank universities using criteria like teaching quality, reputation, and the extent of internationalization, as well as the qualitative and quantitative impact of their research. One goal of the rankings is to boost the research output of Emirati institutions, which is comparatively low by global standards given the high level of economic development of the UAE.

International University Rankings

Despite this lackluster research output, the UAE is fairly well represented in international university rankings compared with other Arab countries, and has advanced in these rankings over the years. There are currently four Emirati universities among the top 30 institutions in the Times Higher Education (THE) Arab world rankings, including the second-ranked Khalifa University, compared with nine Egyptian and five Saudi Arabian institutions. The top Emirati institutions in the current 2018 THE global ranking are the Khalifa University of Science and Technology at position 301–350 (up from 501–600 in 2017), UAE University (501–600), the American University of Sharjah (601–800), and the University of Sharjah (appearing in the THE ranking for the first time in 2018 at position 801–1000).

In the QS Arab Region University Rankings of 2018, seven Emirati universities are featured among the top 50 institutions, compared with nine Saudi Arabian institutions, seven Egyptian universities, and seven Lebanese universities. The top-ranked HEIs in the current QS 2019 global ranking are largely the same as in the THE ranking: Khalifa University (position 315), UAE University (350), the American University of Sharjah (376), the American University in Dubai (561–570), and the University of Sharjah (651–700). No Emirati universities are featured in the current Shanghai ranking, where few institutions from Arab countries appear among the top 1,000.

Education Spending

Despite the fiscal pressure of falling crude oil prices in recent years, education spending in the UAE is quite high. While the country presently spends only about 1.6 percent of its GDP on education (far below the OECD average of 4.5 percent), actual spending per public-sector student is well above the OECD average when adjusting for the small number of Emirati students and the large size of the private sector in the UAE. “Accounting for these differences, the UAE’s public education spending exceeds that in the OECD countries with the highest levels of public education spending (Norway, Denmark, Finland). Expenditure per student is above $22,000, more than twice as in the average OECD economy” (International Monetary Fund).

In fact, the UAE spends more of its government budget on education than all other Persian Gulf countries except for Saudi Arabia. Reflecting the importance of education in the Emirates, 20.5 percent of the federal government’s 2017 operating budget is dedicated to education (10.2 billion dirham or approximately USD$2.78 billion), a far higher percentage than education budgets in countries like the U.S. or Germany.

For the 2018 fiscal year, that allocation further increased to 10.4 billion dirham (17.1 percent of the overall budget). That said, the rapidly growing number of students in the UAE is straining public finances, making greater fiscal allocations necessary to sustain enrollment growth at public universities in the years ahead. The IMF also noted in 2017 that high spending levels in the UAE “…have not yet translated into strong outcomes. For example, the UAE’s PISA scores are at the bottom of those in the OECD economies. Importantly, in all subjects over 40 percent of students are at or below level 2—a proficiency level deemed by the OECD as necessary to participate fully in a globalized world.” As mentioned before, the research output of Emirati universities also remains comparatively low.

The Degree Structure

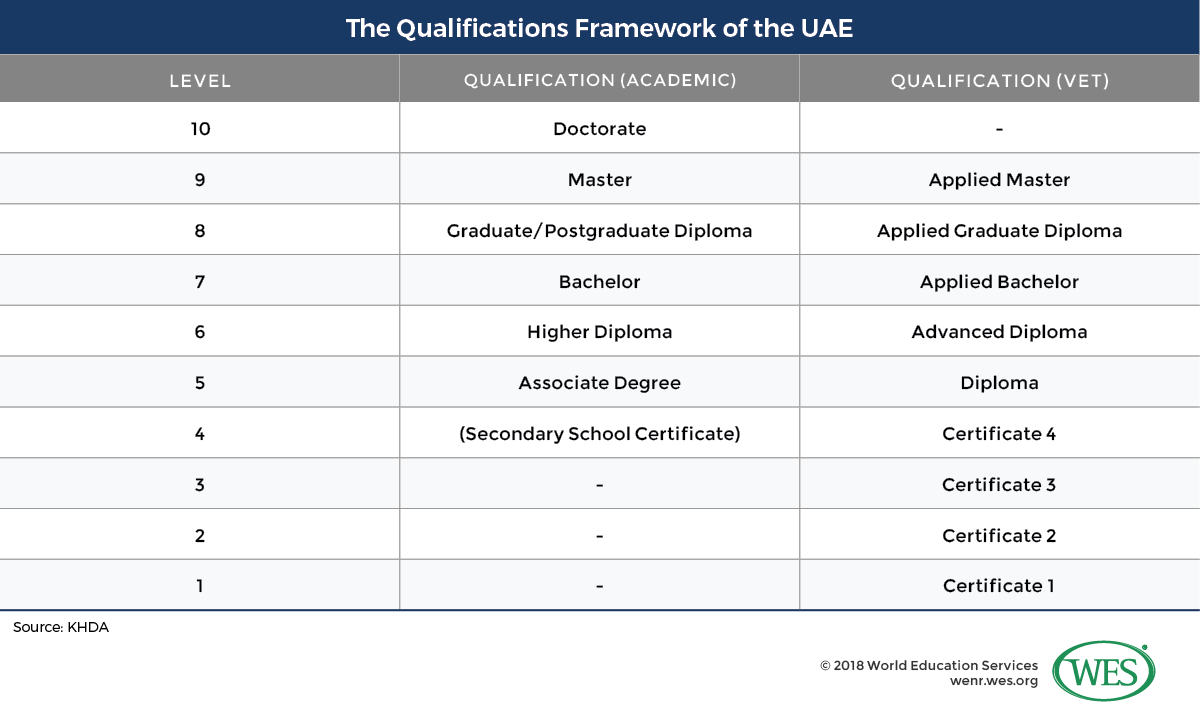

The UAE recently created a national qualifications framework (QFEmirates) in order to benchmark qualifications, define learning outcomes, ease the transfer between academic programs, and facilitate the international recognition of Emirati credentials. (For more information, see KHDA, NQA and CAA). The framework includes 10 levels of qualifications as illustrated below.

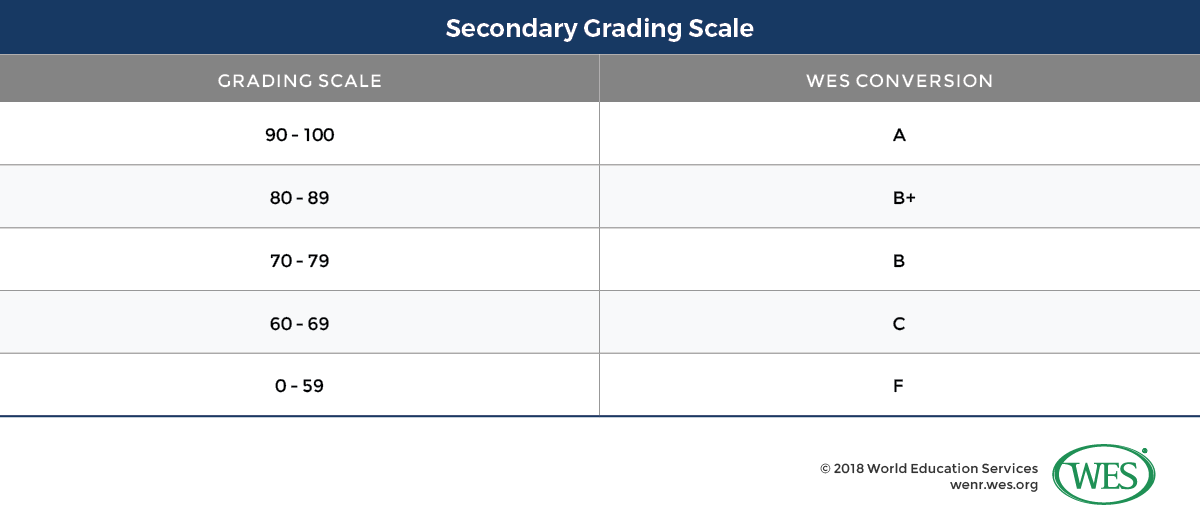

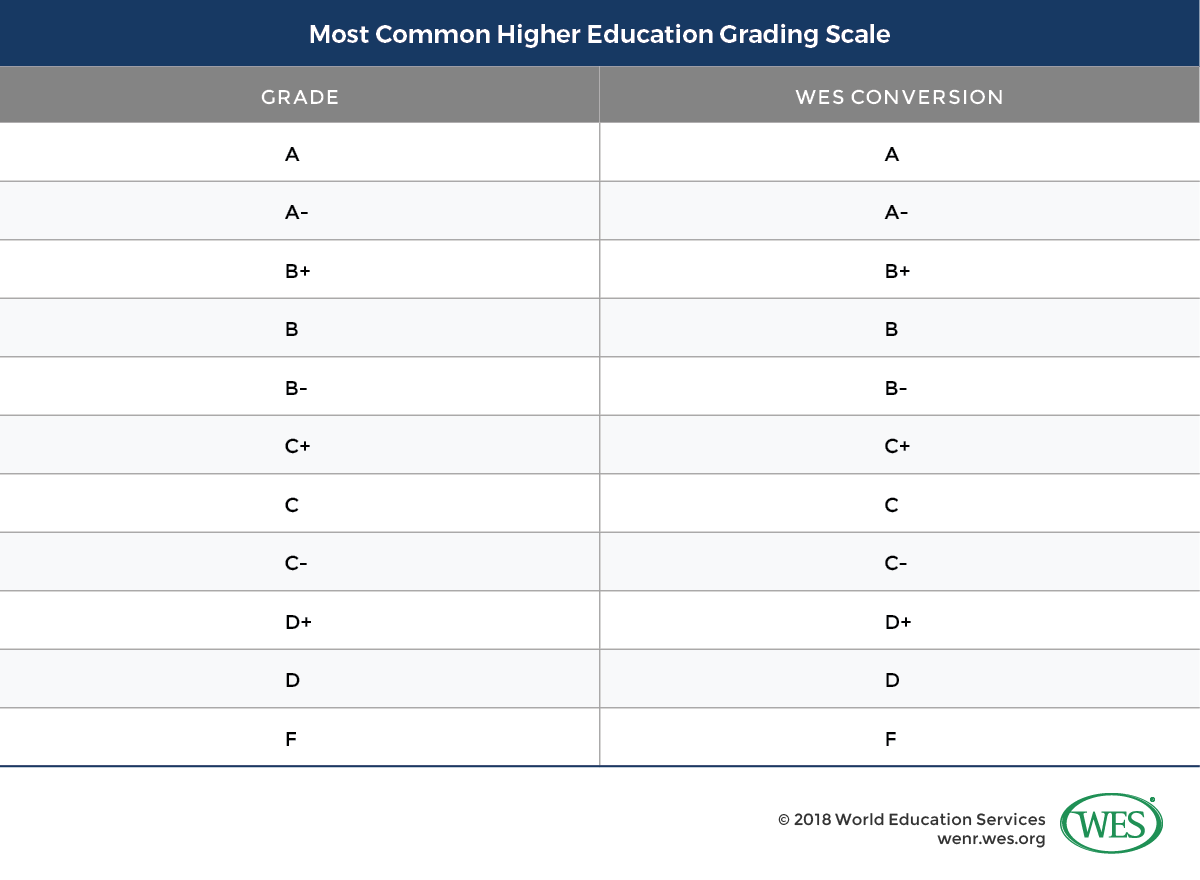

Grading scales in the UAE differ from institution to institution, but the one most commonly used is a U.S.-style A to F scale. The credit system used by most institutions, likewise, closely resembles the U.S. system, with 30 credit hours representing one year of full-time study at the undergraduate level.

Associate Degrees, Diplomas, and Higher Diplomas

The first standard post-secondary credential in the UAE is the associate degree or two-year diploma, formally pegged at level 5 of the qualifications framework. Associate degrees and diplomas are mostly awarded by private colleges and constituent colleges of the HCT. Admission to all HCT programs requires, at minimum, the General Secondary Education Certificate with a minimum score of 60 (70 for engineering), as well as an EmSAT English score of 1100 or equivalent. As of this writing, students who have lower scores still have to complete a foundation program before they begin their studies. However, as mentioned above, the foundation year is currently being phased out.

While diploma programs may be structured as standalone programs, HCT colleges also award these credentials as exit qualifications in incomplete bachelor’s degree programs. The award of a diploma or associate degree usually requires at least two years of study (60 credit hours or more), and a minimum cumulative GPA of 2.0 or higher. Three-year Higher Diplomas awarded by the HCT, on the other hand, require three years of study (90 credits, and also a minimum cumulative GPA of 2.0). The curricula, like those of bachelor’s degree programs, include a general education component in addition to core courses and electives in the chosen specialization. Credits earned completing a course of study toward a diploma or associate degree can often be transferred to bachelor’s degree programs, depending on the institution and the major. Shorter, one-year diploma alternatives also exist, and higher/advanced diploma options may be offered as one-year (2+1) programs entered on the basis of a previous diploma or associate degree.

Bachelor’s Degree

Studying for a bachelor’s degree in a standard academic discipline takes four years to complete (between 120 and 140+ credits, depending on the major). A bachelor’s in engineering and architecture, on the other hand, commonly takes five years. Curricula feature a mandatory general education component, along with core courses and electives specific to the major. Some programs include internships. Common credentials awarded by universities include the Bachelor of Arts and Bachelor of Science, whereas more vocational programs offered by the HCT and other institutions lead to the Bachelor of Applied Science. Admissions requirements vary by institution, but usually include at least the General Secondary Education Certificate and proof of English language competency. As outlined in the university admissions section above, however, many HEIs’ admissions requirements are much more stringent.

Master’s Degree and Postgraduate Diploma

Master’s degree programs are usually research-oriented. Typically offered at universities, they take one to two years of study (30 to 48 credits). To be admitted to the federal UAE and Zayed universities, applicants must have a bachelor’s degree from an accredited institution, a minimum cumulative GPA of 3.0, and demonstrated language skills. Master’s curricula are generally specialized and may involve writing a thesis or completing a research project, although purely course work-based programs also exist.

In addition to offering master’s programs, some universities offer shorter term, one-year courses of study that lead to a postgraduate or graduate diploma. These qualifications are usually more employment-geared and are awarded mostly in professional disciplines. In some instances, credits earned in these courses can be transferred to related master’s programs.

Doctoral Degrees

The standard doctoral degree in the UAE is the Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.)—a terminal research degree that takes between three and five years to complete. UAE University requires a master’s degree with a minimum undergraduate cumulative GPA of 3.3 for admission into its doctoral programs. As in the U.S., these programs typically require the completion of approximately two years of course work followed by the preparation and oral defense of a dissertation. A number of professional doctorates like the Doctor of Business Administration are also awarded.

Medical and Dental Education

Professional entry-to-practice degrees, like the Doctor of Medicine, Doctor of Dental Surgery, or Bachelor of Dental Surgery, are earned after completing five- or six-year-long, single-tier degree programs after high school. Admissions requirements for these programs vary by institution, but are typically competitive. UAE University, for example, requires that applicants sit for the Medical College Admission Test for High School Candidates (MCAT-H), administered by the UK-based company Pearson. Applicants must also have a high school average of 85 percent.

Medical and dental education usually requires two years of premedical study in science subjects, three to four years of professional study, and a passing score on a final examination, followed by a mandatory one-year clinical internship. To practice, graduates must be licensed by the federal Ministry of Health, or in the case of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, the Dubai Health Authority and the Abu Dhabi Department of Health. Licensure in medical and dental specialties requires another three to six years of clinical study and training, depending on the specialty. (See also the UAE Unified Healthcare Professional Qualification Requirements.)

Teacher Education

Until recently, regulations for teachers in the UAE varied by jurisdiction, but teachers at all levels, from kindergarten to high school, are required to have a four-year Bachelor of Education degree. Alternatively, graduates in other disciplines can earn a teaching qualification by completing a one-year postgraduate diploma program in education. In its efforts to improve and standardize its teacher training, the UAE in 2018 introduced a mandatory nationwide teacher licensing system (TLS). By 2021, to obtain a license all teachers in public and private schools will need to pass licensing examinations in pedagogy, English, and the subjects they teach. The licenses will be valid for one to three years, depending on test scores and experience.

Candidates who fail will be required to complete additional training. In a pilot phase, less than 50 percent of candidates passed the tests. Holders of foreign teaching qualifications will have to apply to have their credentials attested and vetted for “equalization.” To obtain a license, foreign-educated teachers will also have to pass the IELTS English language test at a score no lower than a specified minimum, as well as pass additional exams in the subjects of ethics and professional conduct.

Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET)

The UAE presently aims to expand its TVET sector to develop a better skilled workforce. According to the Emirati government, the “… UAE needs to produce 10 Emiratis with vocational skills for every university graduate … to achieve a sustainable and diversified knowledge-based economy. Therefore, it focuses on building a national system to ensure quality technical and vocational education and training (TVET) system.”

To that end, the UAE created a federal Vocational Education and Training Awards Council (VETAC) under the National Qualifications Authority (NQA), established in 2010. The NQA is tasked with building a comprehensive, industry-focused TVET system and providing quality control of TVET providers. VETAC vets and approves vocational qualifications based on occupational skills standards benchmarked in the National Qualifications Framework. In 2014, VETAC authorized the Abu Dhabi Centre for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (ACTVET) to develop and award vocational credentials in Abu Dhabi and the northern emirates, and approved KHDA to do the same in Dubai. Clearly defined program structures and learning outcomes for specific TVET qualifications can be found on ACTVET’s website. A list of approved training institutions and qualifications is provided by VETAC.

TVET credentials in the UAE range from certificate, diploma, and advanced diploma programs to applied bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Certificate and diploma programs are offered at institutions like the Abu Dhabi Vocational Education and Training Institute, or the National Institute for Vocational Education in fields like office administration, human resources, travel and tourism, retail, information technology, and health and safety. Institutions like the HCT and the Emirates Aviation University offer applied vocationally geared bachelor’s and master’s programs in fields like aviation maintenance engineering or marine engineering technology.

WES DOCUMENT REQUIREMENTS

Secondary Education

Examination Results (for the General Secondary Education Certificate etc.) – sent directly by the Ministry of Education

Higher Education

Academic Transcript issued in English – sent directly by the institution attended

For completed doctoral programs: a written statement confirming the award of the degree – sent directly by the institution attended.

SAMPLE DOCUMENTS

Click here for a PDF file of the academic documents referred to below.

- General Secondary Education Certificate

- Two-Year Diploma

- Bachelor of Arts

- Bachelor of Civil Engineering

- Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Surgery

- Graduate Diploma

- Master of Science

- Doctor of Philosophy

1. Rentier states are countries that receive substantial revenues from other countries in exchange for the rentier state’s natural resources (petroleum or other). Rentier state economies rely heavily on external rent and have less need for a strong domestic economic sector. The government is the main recipient of the external rent.

2. For a comparison of TNE in the UAE and China, see the reports on the UAE and China published by the British Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education.

3. Older students who graduated before the introduction of standardized tests in 2003 may be admitted based on scores in the General Secondary Education graduation examination.

4. The share of private enrollments varies by emirate. It made up 64 percent in Abu Dhabi, 78 percent in Sharjah and 70 percent in Ajman in 2014, but only 41 percent, 40 percent and 28 percent, respectively, in Umm Al Quwain, Ras Al Khaimah and Fujairah.